“I once wanted to become a teacher, maybe even a professor, but my dreams changed,” shared Mr. Umaru, a resident of a leprosy colony in Ebute Metta, Lagos State. “I completed secondary school in 1994, but this illness started around 1987, even before I finished my studies.”

Across Nigeria, thousands of individuals who have survived leprosy, along with their families, endure daily life marked by poverty, neglect, and the painful realities of stigma and discrimination. According to The Leprosy Mission Nigeria, over 3,000 people are living with the long-term consequences of leprosy in organised colonies—facing not only health challenges and psychological trauma but also limited access to basic services.

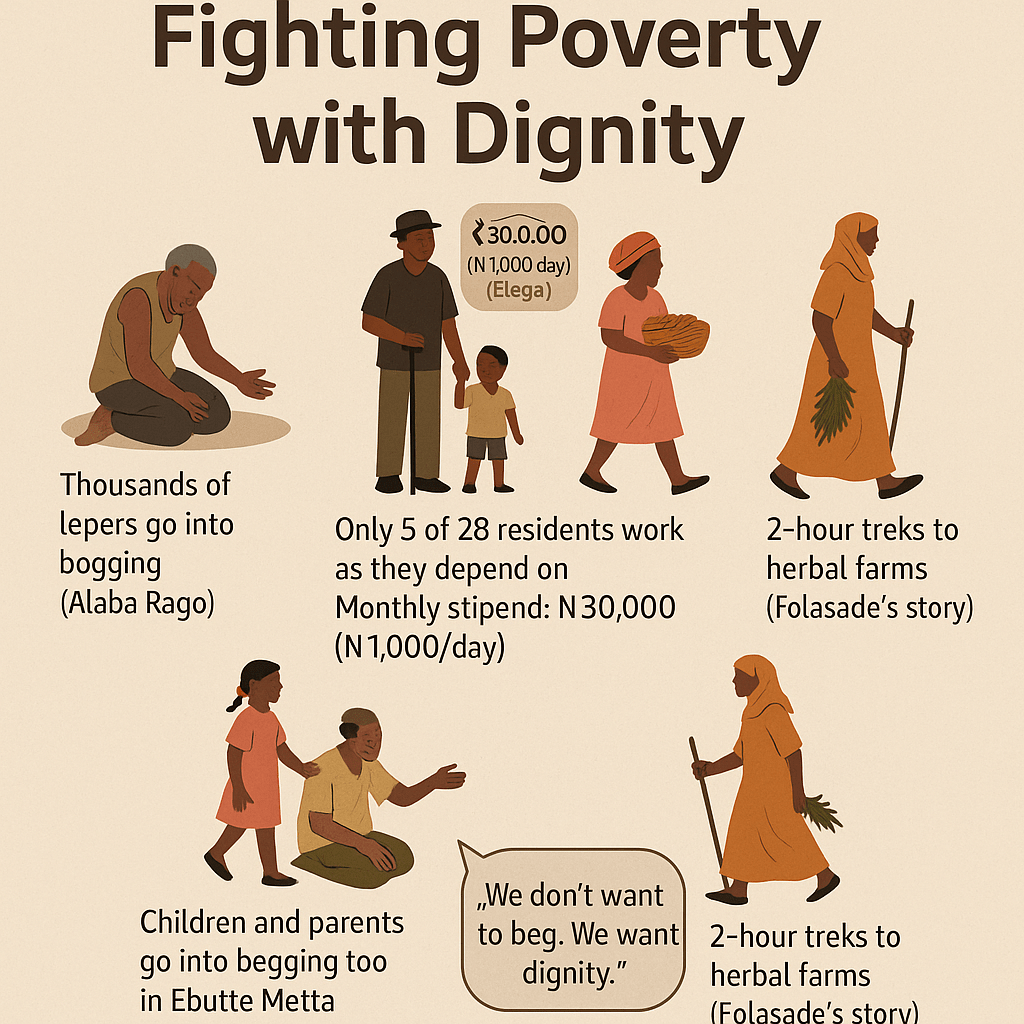

Healthcare for these communities is often scarce. Women give birth without trained medical assistance, and many children are deprived of education. As a result, parents resort to begging while their children sell items along busy roads, a reflection of society’s widespread neglect.

Nigeria reportedly records at least 2,500 new cases of leprosy annually, and the nation hosts more than 61 leprosy settlements scattered across various states, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic infectious illness caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. The disease typically affects the skin, nerves, upper respiratory tract, and eyes, and is transmitted through prolonged close contact, most commonly via respiratory droplets.

Contrary to longstanding myths, leprosy is not highly contagious and is curable when detected early. The WHO recommends multi-drug therapy (MDT), a regimen provided for free in many countries, including Nigeria. However, stigma and inadequate health infrastructure mean many cases go untreated, trapping people in avoidable suffering.

During recent visits to four leprosy colonies—Alheri in Abuja, Elega in Ogun State, and Ebute Metta and Alaba Rago in Lagos—the struggle for survival, dignity, and societal recognition was alarming and ongoing.

In these settlements, daily life is both a physical ordeal and an emotional battle. Despite being the country’s capital, Abuja, together with Lagos State—which hosts three leprosy colonies—reportedly houses some of the nation’s most impoverished leprosy survivors.

In Alaba Rago—a densely populated settlement and dumpsite in Lagos State’s Ojo Local Government Area—over 2,000 leprosy survivors reside. The settlement lacks electricity and depends on a single borehole donated in 2008 for water. Open defecation is widespread, and with no nearby public hospital, pregnant women often give birth at home under unsafe conditions.

“If it’s a serious health case, we try to call in private doctors and raise money by begging on the streets,” explained Umar Abdulrahim, a former teacher from Kano State now living in the Lagos colony.

Abdulrahim, a father of eight, once worked as a teacher for a decade before losing his job in 1981 due to his illness.

At Ebute Metta, roughly 200 residents live in deteriorating shacks. Many community members are blind or have mobility impairments, with only a handful able to work for income.

The colony’s population, aged mostly between 45 and 75, faces the harsh reality of having to send their children to beg on Lagos streets just to survive.

After finishing secondary school, Mr. Umaru went on to college, but leprosy and social rejection pushed him off his intended career path. Arriving in Lagos in 2000, he now depends on begging for daily sustenance, sharing a home in the Ebute Metta colony with his wife and seven children.

Within the settlement, deep-rooted issues extend beyond poverty. Toilets are scarce and often unfit for use. During the rainy season, overflowing soakaways create additional health risks. Elderly residents may have to crawl or rely on others to access toilets, while children—some left to bathe outdoors—may go missing altogether.

“There’s no organised system here,” said Ahmad Abubakar, the colony’s community leader. “If someone helps you reach the toilet, good. If not, you crawl. That’s just how it is here.”

Many in the settlement feel forgotten by government authorities. “The last time we received regular support was during the military era, when food aid came every month,” Mr. Abubakar recalled. “Now, we wait months and hear nothing.”

Established in 1997 as a haven for leprosy survivors displaced from Kano, the compound now suffers from severe neglect: cracked walls, leaking roofs, and vanishing government support.

“If only they’d repair our buildings and help our children with their schooling, things would change,” said one woman in Hausa, holding her baby. “We just want to live with dignity.”

The segregation of people with leprosy, once practiced in Nigeria and other countries, is now widely condemned by health professionals and international organisations. The World Health Organization and The Leprosy Mission maintain that forcibly isolating patients not only violates their rights but also reinforces negative stigma. These groups recommend community-based care, social reintegration, and equal access to healthcare and education instead.

Yet, many Nigerian leprosy colonies remain active—some for decades—due to weak policy implementation, entrenched stigma, and a lack of rehabilitation and reintegration programmes.

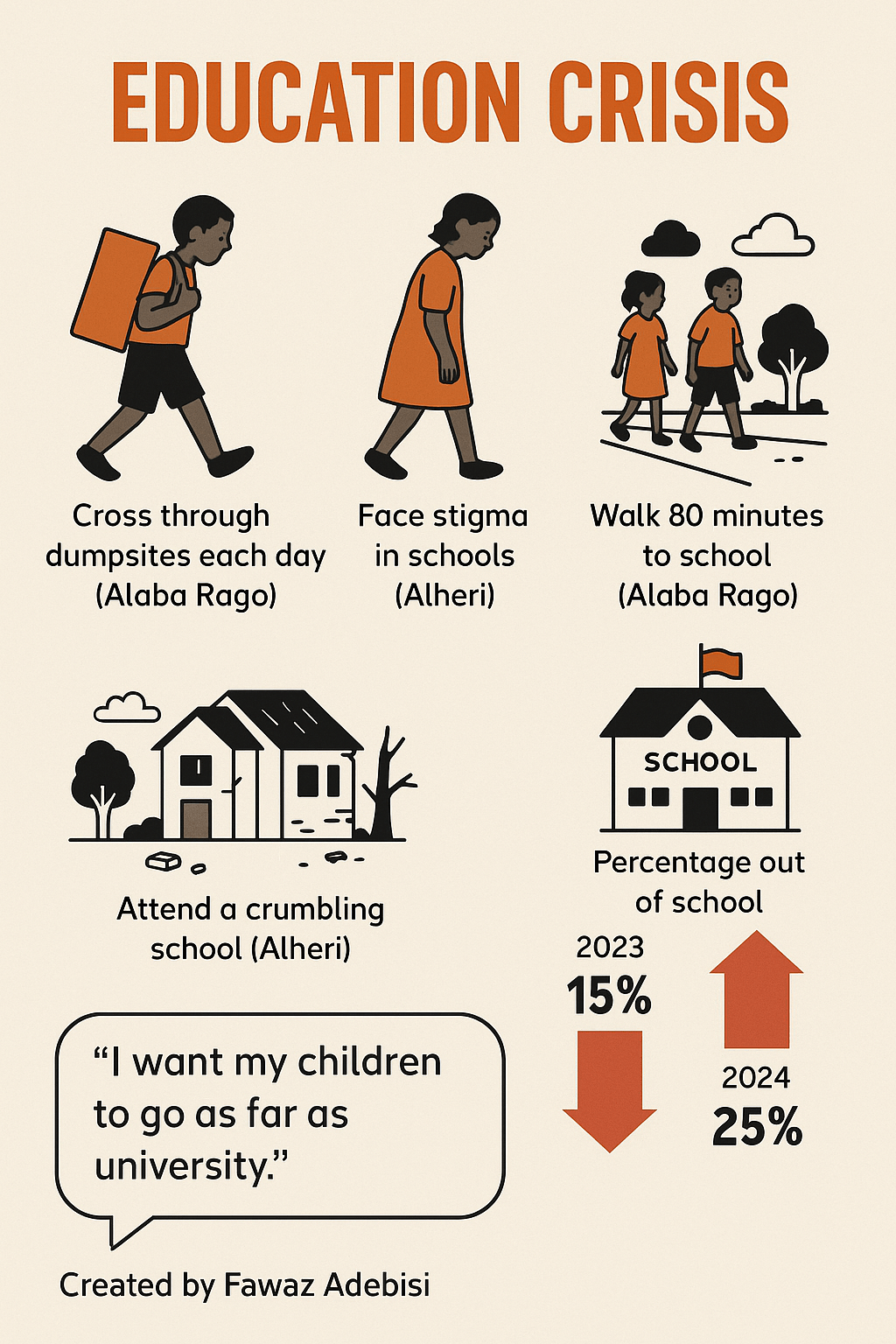

Access to education is a major concern for leprosy survivors, especially in colonies in Ogun State and Abuja. While some colonies have nearby public primary schools, most children do not continue to secondary school, mainly due to financial hardship.

“We’re struggling just to survive, so there isn’t enough to fund school beyond the primary level,” said Folorunsho Lukman, secretary of the Elega Leprosy Colony.

Abubakar recalls how his children attend public school, but obstacles remain. “My eldest is about to sit for the junior secondary exams, but we need ongoing support to make sure all my children go far in school,” he explained.

Children living in Alaba Rago must walk up to 80 minutes into town to attend classes, only to experience discrimination linked to their parents’ illnesses.

“Our children attend Ajegunle Government Primary School, but some drop out after being mocked,” lamented another resident. “Many of these kids are perfectly healthy but lose confidence and stop attending school because of the way society treats them. We try to reassure them that education is their only future, even when we’re gone.”

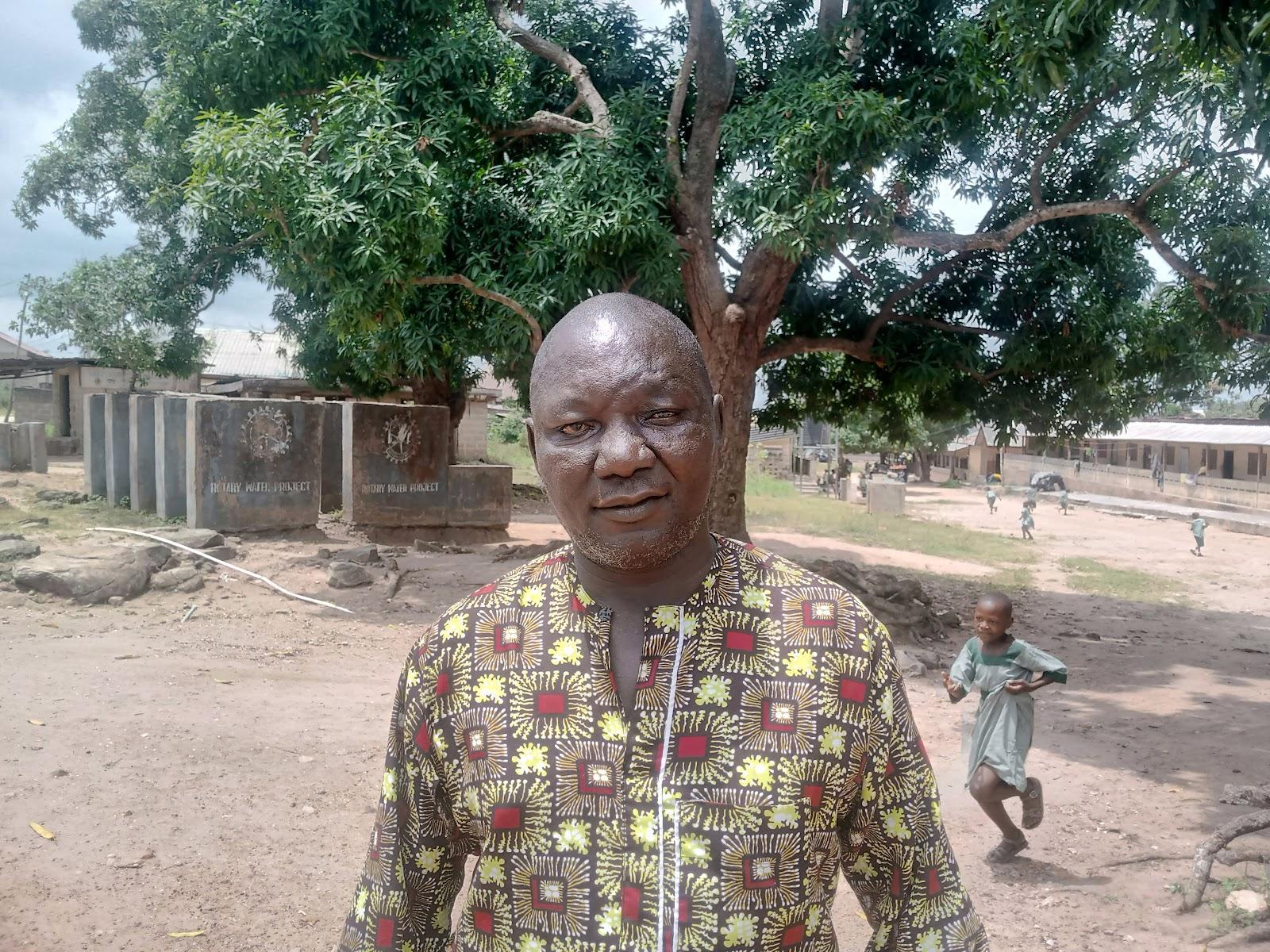

Conditions in some schools remain challenging; for example, at Alheri public school, only one of the five buildings is considered usable.

The situation in Ogun State shows some initiative. The Elega colony operates under a policy that forbids begging, aiming to preserve dignity. “We don’t want any of our members to have to beg for survival,” said Jimoh Hammed, Elega’s chairman.

Yet, with limited work opportunities, only five out of the 28 leprosy survivors there have jobs. Two residents, including Hammed and Lukman, drive taxis; three others sell herbs.

Folasade Olanrewaju, a mother of three enduring chronic leg pain, makes a living selling herbs. “I give my daughter ₦1,500 daily for school—she eats when she returns. I struggle so she won’t have to beg,” she said.

“Sometimes, it takes me two hours to trek to the farm, and I often need to stop and rest because of my bad leg. But I keep going,” Olanrewaju added.

She spends over ₦90,000 per term on her child’s education. “If there’s work that doesn’t stress my leg, I’ll gladly switch,” she said with determination.

Idowu Abudu, also known locally as Iya Eleko, has lived at Elega for over twenty years. She continued making corn pap to support her five children, but the smoke has damaged her eyesight. “I can’t stop because my children depend on me,” she said. She now supplements her income by selling herbs.

Those who can work support others, ensuring the community’s policy of dignity is upheld. However, children continue to hawk wara (local cheese), doughnuts, and other snacks to supplement family incomes. In other settlements, such as Ebute Metta and Alaba Rago, begging remains prevalent due to lack of alternatives.

To ease their burden, the Ogun State Government increased monthly stipends for each adult in the colony to ₦30,000 in March 2024, up from ₦10,000. However, many say this does not stretch far enough for their families’ needs.

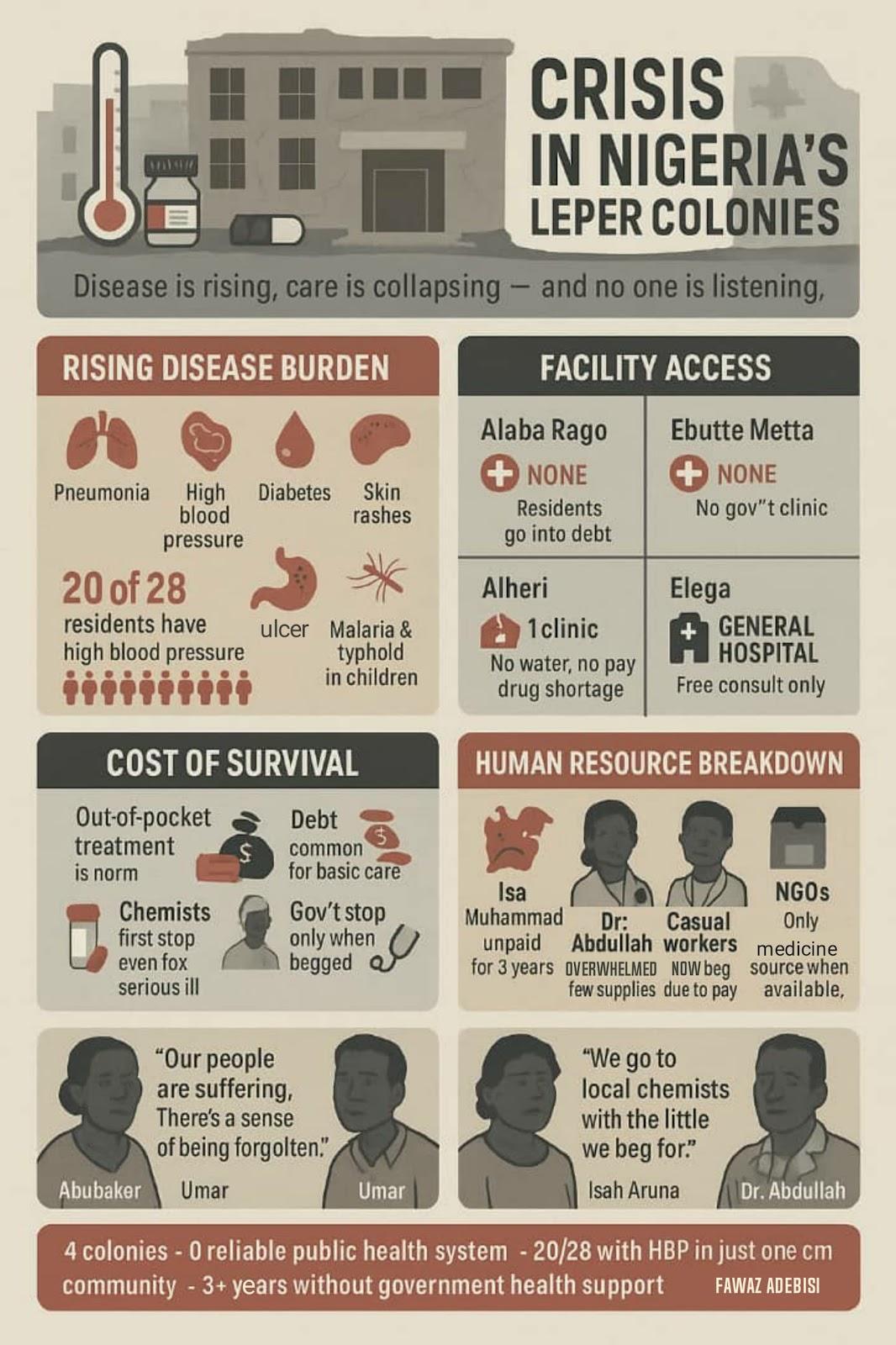

Health issues like skin rashes, ulcers, pneumonia, high blood pressure, muscular disease, coughs, and diabetes are rampant in all four colonies visited for this report. Yet, public health facilities are absent in places like Alaba Rago and Ebute Metta; residents either self-medicate or travel long distances for treatment.

“There is much suffering here. We lack basic food, clothing, education, and healthcare,” lamented Abubakar. “We feel forgotten.”

Mr. Umaru added, “If we fall sick, we go to local chemists and pay from what we’ve begged for, and only sometimes does the government help if the illness is severe.”

Ironically, at Elega in Ogun, a general hospital stands within the settlement, but most residents are reportedly left without drugs or free care. A hospital-employed health officer, who asked to remain anonymous, explained that children often battle malaria and typhoid, while high blood pressure is common among adult residents.

“We can only listen to their complaints for free; otherwise, they pay for doctor services and drugs,” the health officer confirmed.

Conditions in Abuja’s Alheri colony are similarly dire: the only health centre is decaying, with rising rates of pneumonia, skin issues, and other illnesses, but little to no medical supplies.

Isah Aruna, an Alheri resident, displayed scars along his arms. “The itching is terrible; sometimes it bleeds,” he said, voice quivering.

Much of the burden falls on volunteers and low-paid workers. Salisu Aruna, a doctor, said, “We rely on NGOs for medicines, but supplies often run out fast.” Most workers have not been paid in years.

Isa Muhammad, an unpaid staff member, said, “We haven’t seen government support for years.”

Hussein Shinkoso, a carpenter and clinic worker, expressed similar frustrations: “The Leprosy Mission Nigeria assisted before, but not anymore. Even basic equipment would help us earn a living,” he told this reporter.

Mallam Adamu, an elderly ulcer patient, raised another key need: “It’s been a long time since we got new shoes. That support would make a real difference.”

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are stepping in to fill the gaps left by government inaction, though resources are often limited and inconsistent.

At Elega, Mr. Lukman noted, “Groups like Lions Club, Rotary Club, Mace Club, and several NGOs regularly support us. Some even helped install solar power for our water supply.”

In Abuja, the Leprosy Mission Nigeria’s FCT branch continues to support Alheri residents, providing medical treatment, footwear, and mobility aids, according to residents and the group’s programme officer, David Aire.

“We’ve treated and cured individuals, provided shoes, protective gear, and crutches for amputees,” Aire explained.

Healthcare workers stress that without urgent action, conditions could further deteriorate in Nigeria’s leprosy colonies. Many suffer from chronic illnesses, and the breakdown of drug supply chains and medical staffing only worsens the threat to their lives. For example, a March 2025 report alleged that Nigeria’s stockpile of multi-drug therapy for leprosy—the global standard treatment—was depleted for nearly a year, leaving thousands without essential medicines.

Doctors at ERCC Hospital in Nasarawa reportedly observed a rise in amputations and irreversible nerve damage due to treatment delays. “Once fingers are lost, they’re gone for good,” lamented one staff member, highlighting the human cost of inadequate care.

Staff at settlements like Alheri face mounting workloads and low morale. Their only clinic is crumbling, water is scarce, and both paid and casual staff have not received government salaries in years—pushing some to neglect their work or turn to begging.

“Most of our cases are malaria and pneumonia. Others have hypertension or chronic ulcers. When cases are severe, we refer patients to Kwali General Hospital,” said Dr. Muhammed Abdullah, who works at the Alheri clinic. “But we need more drugs and government support. We’ve not had government assistance in three years.”

The situation is so dire, Abdullah added, “Even cleaner staff have stopped working, because they’re not paid. Sometimes, you’ll see the clinic dirty and abandoned.”

The WHO’s Global Leprosy Strategy 2021–2030 aims for early detection, zero discrimination, and integration—calling for an end to long-term segregating colonies. A United Nations Human Rights report from 2022 condemned forced isolation as a violation of international rights and advocated for the dismantling of such camps in favour of inclusive protections.

UN Special Rapporteurs have repeatedly warned that the poor healthcare infrastructure in colonies undermines both human rights and public health security. Unless urgent reforms happen, medical experts warn, curable diseases will continue to cause untold suffering in Nigeria’s most marginalised communities.

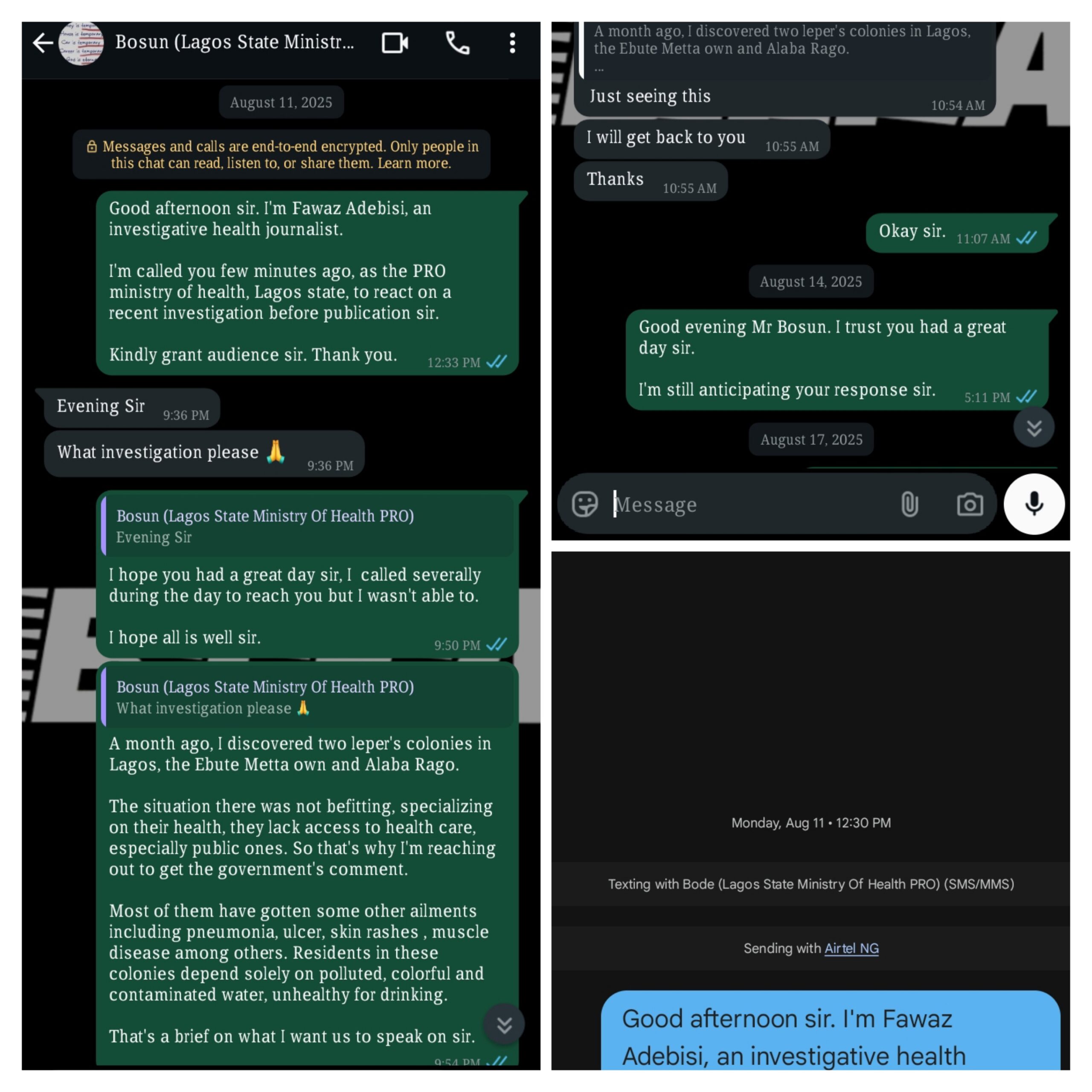

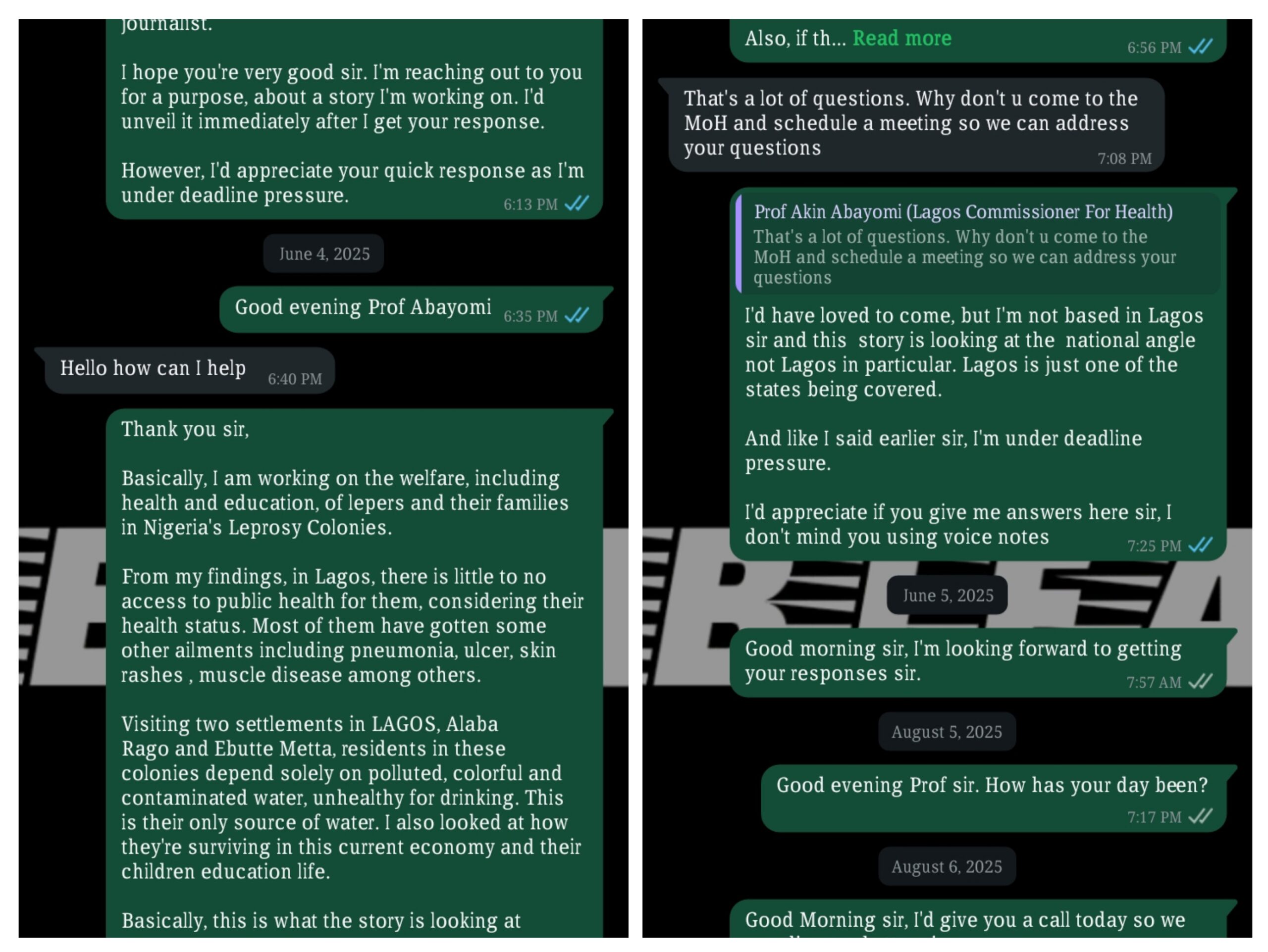

The governments of Lagos and Ogun states have reportedly not issued public responses to the conditions within their leprosy colonies. When approached by this reporter, Lagos State’s Commissioner of Health, Akin Abayomi, requested an in-person interview, but due to logistical challenges, follow-ups reportedly went unanswered. Similarly, the Director of Public Affairs at Lagos State’s Ministry of Health, Olatunbosun Ogunbanwo, and Ogun State’s Commissioner of Health, Tomi Coker, did not respond to repeated enquiries.

When federal authorities were contacted, responses were similarly limited. After multiple visits and phone calls to the Ministry of Health, a single official offered a vague assurance of ongoing efforts but provided no details or names.

The Special Assistant to the Mandate Secretary for Health and Environmental Services in the FCT suggested that all questions be directed to Dan Gadzama, Director of Public Health. Mr. Gadzama, when reached, stated that he could not release any information without clearance, only saying, “Work is ongoing, and we’ll get back to you soon.” In a follow-up text, he thanked this reporter for raising awareness about the plight of the leprosy-affected communities.

The prevailing silence from multiple levels of government highlights a troubling pattern. For those living in Nigeria’s leprosy colonies, the fundamental rights to healthcare, inclusion, and dignity remain, for now, out of reach.

What steps do you think Nigerian authorities and communities can take to ensure dignity, health, and integration for leprosy survivors and their families? Should more be done to break the cycle of stigma and neglect in marginalised settlements?

Share your thoughts in the comments or connect with us on social media! If you have a story, tip, or opinion to share—or if you’d like to get your own story featured or sold—please email us at story@nowahalazone.com.

For general support, reach us at support@nowahalazone.com.

Follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter) and Instagram for the latest updates.