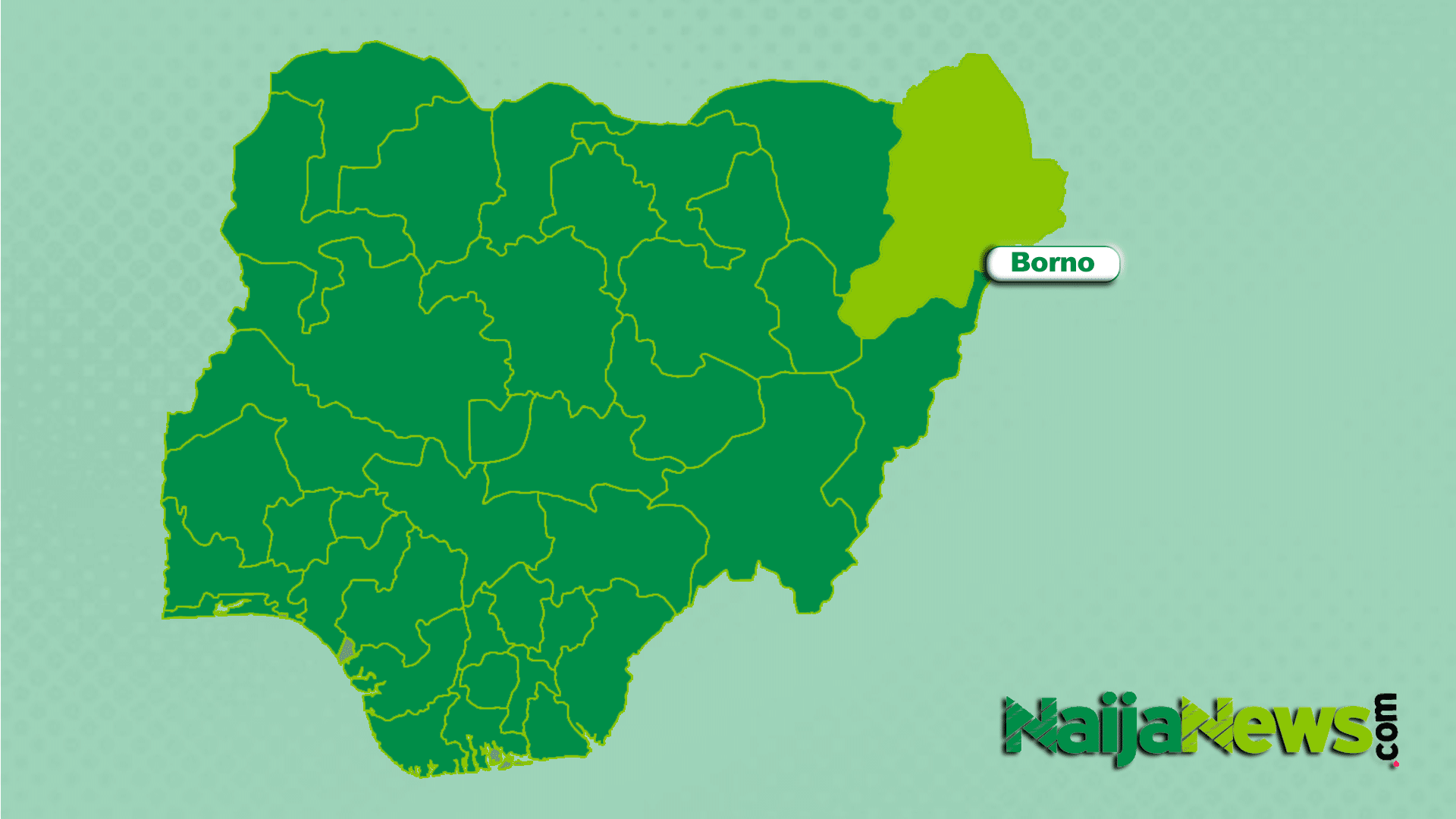

Nearly thirty years after violence shook the communities of Ife and Modakeke in Osun State, quiet streets and overgrown compounds still bear the scars of conflict. For survivors and their descendants, the trauma endures—silent yet ever-present, woven into daily life and collective memory. This article explores the lasting impact of the infamous Ife–Modakeke crisis and ongoing calls for healing, providing important context for readers in Nigeria, West Africa, and beyond.

In the late 1990s, the ancient towns of Ife and Modakeke became synonymous with one of Nigeria’s most enduring intra-ethnic conflicts. Though the violence has long since stopped and news headlines have faded, the aftermath remains visible in abandoned properties, skeletal homes reclaimed by nature, and a community navigating both sorrow and hope. Children, whose only experience of the war comes from family stories, walk silently past ruins—reminded of unreconciled losses and lives disrupted.

As reported by sources, the conflict did not follow traditional battle lines. Instead, it unfolded within neighbourhoods and farmlands, affecting people of every age and background. The Nigerian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Ibadan estimated that more than 2,000 lives were lost during the 1997–2000 outbreaks alone. Most of the casualties, according to local records, were civilians caught in unexpected clashes, with homes quickly turning into battlegrounds and families forced apart.

The repercussions went beyond lost lives and destroyed property. Relationships and trust fractured in homes where Ife and Modakeke families had shared years of kinship and cooperation. As one survivor, quoted in The Guardian (Nigeria), observed: “It was not just buildings destroyed, but bonds of love and trust as well.” Even now, fear and suspicion sometimes resurface, despite a general return to peace.

Despite nearly three decades passing, reconstruction has lagged, and official support remains limited. Many buildings damaged during the conflict in areas like Isale Agbara, Oke Eso, and Surulere are still uninhabitable, their shells either abandoned or overtaken by weeds. Some locals, according to sources, say these ruins have become sites for illicit activity, raising fresh security concerns. Community leaders and residents have voiced repeated calls for meaningful intervention and compensation, claiming that promised government assistance has yet to materialise.

In the words of Adekunle Ogunbiyi, 48, whose home in Oke Eso remains unrepaired: “My father lost everything. We’ve not been able to rebuild … there’s simply no money.” Stories like Ogunbiyi’s echo across the affected neighbourhoods, reflecting a widespread sense of abandonment. Some survivors have resorted to selling their property at a fraction of its value to developers, reportedly accelerating urban renewal but erasing layers of local history and emotional heritage.

For many, the trauma is also financial. Mrs Bose Oyedeji, 51, recounted to The Guardian how her late father lost two houses and, ultimately, his peace of mind: “The war robbed us of everything. My father was never compensated, and the stress and fear hastened his death.” She calls for government-backed reparations, not for vengeance, but to support rebuilding and healing.

Reflecting a sentiment shared by many, another resident, Mr Ayanwale Oluwagbemi, explained: “If there’s no assurance it won’t happen again, what’s the point of rebuilding? But if the government assures us of lasting peace and development, it will give people confidence.” Such statements highlight the complex interplay of memory, fear, and hope that continues to shape community life.

Historically, the Ife–Modakeke conflict is regarded as Nigeria’s longest-running intra-ethnic dispute, as documented in reports spanning back nearly two centuries. There have reportedly been at least seven major eruptions of violence: between 1835–1849, 1882–1909, 1946–1949, 1981, 1983, 1997–1998, and in 2000. The most recent flare-up began in 1997, when local agitation over a separate administrative council reignited tensions. According to official records and subsequent analyses, administrative interventions eventually followed, including the creation of Modakeke Area Office in 2002 and Modakeke’s three electoral wards under Ife East Local Council. Nonetheless, observers, such as the Modakeke Progressive Union (MPU), argue that political compromises have not bridged the gap left by war—a gap characterised by economic hardship and enduring trauma.

Recent field investigations, such as those by The Guardian and local civic organisations, confirm that compensation payments and formal government rebuilding projects remain elusive. While some infrastructural developments have since occurred—new schools, banks, colleges, and hospitals—community members insist that sincere, accountable efforts are still needed to fully restore trust, livelihoods, and social cohesion.

Leading voices in the community, such as Professor Peter Olawuni, National President of the Modakeke Progressive Union, stress the need to pair peacebuilding with reconstruction. “People are happy that peace now reigns, but both communities must stay vigilant—especially the youth,” he told reporters. The Ogunsua of Modakeke, Oba Joseph Olubiyi Toriola, similarly emphasised that while some progress has been made—such as launching Ogunsua Radio for peace education—full reconciliation and adequate compensation remain out of reach for many.

Oba Toriola notes that in other countries, reparations and rebuilding efforts are prioritised after conflict, while “here, we talk about committees, but implementation is the problem.” He urges government bodies to address root causes, offer greater inclusion, and invest in long-term infrastructure instead of one-off payments alone. Both federal and state governments, he said, should do more to ease transportation challenges and promote economic recovery for the growing population.

From the official side, Olawale Rasheed, Chief Press Secretary to the Osun State Governor, stated that the current administration did not previously commit to compensation for crisis victims—claims about such promises refer back to earlier governments. Rasheed added that he would consult with relevant authorities for a more comprehensive response.

Locally, community members express a cautious optimism. Many residents credit traditional rulers—such as the Ooni of Ife, Oba Enitan Adeyeye Ogunwusi, and the Ogunsua of Modakeke—for their role in sustaining peace. Both leaders reportedly meet regularly with elders and youth representatives to resolve disputes swiftly and quietly, using dialogue and community engagement rather than force. Churches, mosques, and youth groups have also played a significant part in spreading messages of unity.

For readers in Nigeria and across West Africa, the experience of Ife and Modakeke offers a valuable lens on reconciliation, infrastructure, and the delicate process of rebuilding after conflict. As other regions on the continent continue to grapple with similar challenges, the lessons drawn from Osun State’s history remain acutely relevant: justice, healing, and inclusive dialogue are essential for any hope of lasting peace.

In conclusion, while progress has been made, many say much work remains—especially in addressing the needs of those most affected and ensuring fairness across all communities. As Nigeria continues to evolve, the legacy of Ife–Modakeke invites us to consider: How can we build stronger, more resilient societies after such deep divisions? Should compensation and active government involvement play a bigger role in collective healing? Share your views below.

Food inquiries: food@nowahalazone.com

General support: support@nowahalazone.com

Story sales/submissions: story@nowahalazone.com

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X (Twitter)

Follow us on Instagram