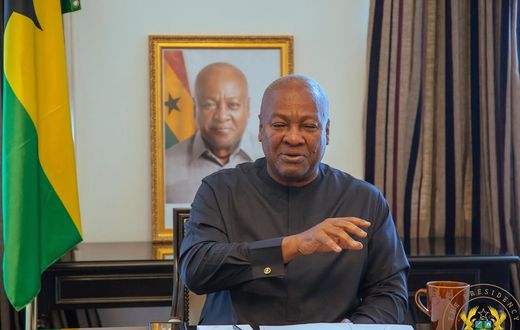

Ghana’s Anti-Corruption Efforts: Mahama Reassures Public as Operation Recover All Loot (ORAL) Faces Scrutiny

In a move closely watched not only in Ghana but across West Africa, President John Dramani Mahama has publicly reinforced his administration’s commitment to fighting corruption through the ongoing initiative known as Operation Recover All Loot (ORAL). According to reporting by local Ghanaian media, Mahama assured citizens during a recent Presidential Media Encounter that no private individual or group would be permitted to undermine ORAL’s mandate to retrieve public funds allegedly mismanaged by former government officials.

President Mahama reportedly emphasized that all cases under active review by the country’s Attorney General will be stringently observed, with the explicit aim of preventing any attempts at shielding individuals from proper legal scrutiny. He stated his determination to ensure that attempts at interference receive zero tolerance from the administration.

These assurances come in response to remarks by Fifi Fiavi Kwetey, General Secretary of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), who recently alleged during the NDC’s 5th Annual General Meeting that certain unnamed persons were seeking clandestine settlements with individuals slated for prosecution under the anti-graft drive. Kwetey’s claims, widely circulated in Ghanaian political circles and picked up by several media outlets, have sharpened focus on ORAL’s integrity and independence.

Fifi Kwetey

Speaking on Wednesday, September 10, at the Presidential Media Encounter—a key public briefing broadcast across Ghana—President Mahama decisively addressed the growing conversation around backdoor negotiations and alleged interference. According to local reports, he declared that his administration would not tolerate any behind-the-scenes dealings that could compromise the justice process. He reportedly called for full transparency in all legal procedures related to ORAL.

Mahama further explained his administration’s approach:

I can assure you that there is no way anybody can interfere. I cannot control people’s thoughts to stop them from attempting to interfere, but I am responsible for ensuring that such interference comes to nothing. That is why I closely monitor and hold regular meetings with the Attorney General.

According to Mahama, he receives regular updates on the progression of investigations linked to ORAL. These briefings, as he explained, provide confidence that each case will advance on its unique merits, rather than personal influence or political considerations.

He stressed to gathered journalists and stakeholders:

I am confident that the cases will go ahead based on their merits and that nobody will have the opportunity to interfere. If anybody goes lobbying or paying people to obstruct justice, they are only wasting their resources. All cases will be investigated and brought to their logical conclusion.

For Nigerians—and indeed many viewers across West Africa—President Mahama’s approach may sound familiar. Regional observers have often drawn parallels between Ghana’s anti-graft initiatives and Nigeria’s own high-profile corruption probes, such as activities by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC). In both countries, efforts to retrieve state assets and prosecute officials have sparked debate about political will, legal bottlenecks, and the transparency of processes.

Addressing concerns from both legal experts and the public over the pace of prosecutions, Mahama explained that the Attorney General is said to be methodically building watertight cases before heading to court. According to Mahama, this diligence is necessary to secure lasting results and minimize the risk of future appeals or dismissals. Critics, however, continue to urge greater speed and less bureaucracy in the handling of high-profile corruption cases—echoing frustrations among Nigerians when anti-corruption efforts appear to stall or lose momentum.

Responding to ongoing concerns, President Mahama clarified the procedural benchmarks set by his administration:

If people are exonerated in the courts, that is what justice is all about. We are doing our part, and we are being painstaking in preparing the dockets. People may complain that it is slow, but you do not want to rush a case to court only to have it thrown out on a technicality. That is why we are making sure that when a docket is prepared, it is watertight enough to secure a conviction.

In line with these statements, government spokespersons have reiterated that every individual implicated in corruption, regardless of status or affiliation, will undergo comprehensive investigation and, if warranted, prosecution, with the possibility of recovery of public funds considered to have been misappropriated. This policy is part of a broader push by Ghana—and mirrored to varying degrees across West Africa—to strengthen accountability in governance and set new standards for public finance management.

Some analysts based in Accra and Lagos have observed that while anti-corruption rhetoric has become a mainstay of political campaigns in several West African states, results often depend on the political independence of investigative bodies, the strength of legal institutions, and the will of leaders to resist political pressure. While supporters of the current Ghanaian government cite the transparency of ORAL as a sign of progress, critics warn that only consistent enforcement and results in courtrooms will fully restore public trust.

International development partners and civil society organizations—including Transparency International and the Ghana Integrity Initiative—have urged all governments in the region to prioritize independence of the judiciary and robust whistleblower protections, noting that such measures are crucial to the credibility of any anti-corruption drive. They have further recommended regular public reporting on recovered assets and the outcome of criminal cases, practices that some say could also benefit anti-corruption agencies in Nigeria and neighboring countries.

On a global note, the effectiveness of West African anti-corruption efforts can influence international perceptions of governance and the ease of doing business in the region, crucial for both Nigerian and Ghanaian aspirations to attract foreign investment. According to the World Bank, countries that demonstrate consistent legal action against graft often see improved investor confidence and more favorable trade agreements, reinforcing why transparent, accountable governance matters beyond national borders.

What’s Your Take? As governments throughout West Africa continue to battle corruption, the question remains: will these high-profile initiatives bring the real accountability that everyday people demand? Do you think anti-corruption drives like Ghana’s ORAL, or Nigeria’s EFCC-led campaigns, are making enough impact? Are there ways they could improve transparency or public trust?

Share your insights—what lessons can other countries, like Nigeria and Ghana, learn from each other to strengthen the rule of law and accountability in governance?

Food inquiries: food@nowahalazone.com

General support: support@nowahalazone.com

Story sales/submissions: story@nowahalazone.com

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X (Twitter)

Follow us on Instagram