Summary

In this essay, the term “Pax Britannia” stands in as a metaphor for the peace, stability, and functional power-sharing arrangements seen within the United Kingdom. It references a system based on meritocracy and realpolitik among Britain’s diverse constituencies and does not denote the imperial dominance or colonial ambitions of the past. While there are nods to British colonial history, this is not the core focus here.

Similarly, “Pax Nigeriana” is invoked as an aspirational model for Nigeria – a vision of lasting stability, social equity, robust economic development, responsible power sharing, and international cooperation, all while protecting Nigeria’s sovereignty and national interests. It’s a call for a merit-based system that secures peace, security, and balanced political participation across the nation’s diverse landscape.

Analysis

Britain presents a relatively homogenous society, home to about 68.3 million people—of which 83% identify as White and 77% as White British or Irish (ONS, 2023). Its Christian heritage has greatly influenced the Commonwealth, and its political system gradually evolved over centuries. Despite being a constitutional monarchy, Britain’s democracy and institutions are in constant dialogue with evolving social, technological, environmental, and legal challenges.

Contrast this with Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, which now exceeds 238 million residents and is on track to reach 400 million by 2050 (World Population Review; The Economist). The country includes over 250 ethnic groups and languages and a wide range of religious traditions—Christianity, Islam, indigenous beliefs, and polytheism—making it a vibrant pluralist state. The Hausa/Fulani dominate the north, the Yoruba the southwest, and the Igbo the southeast.

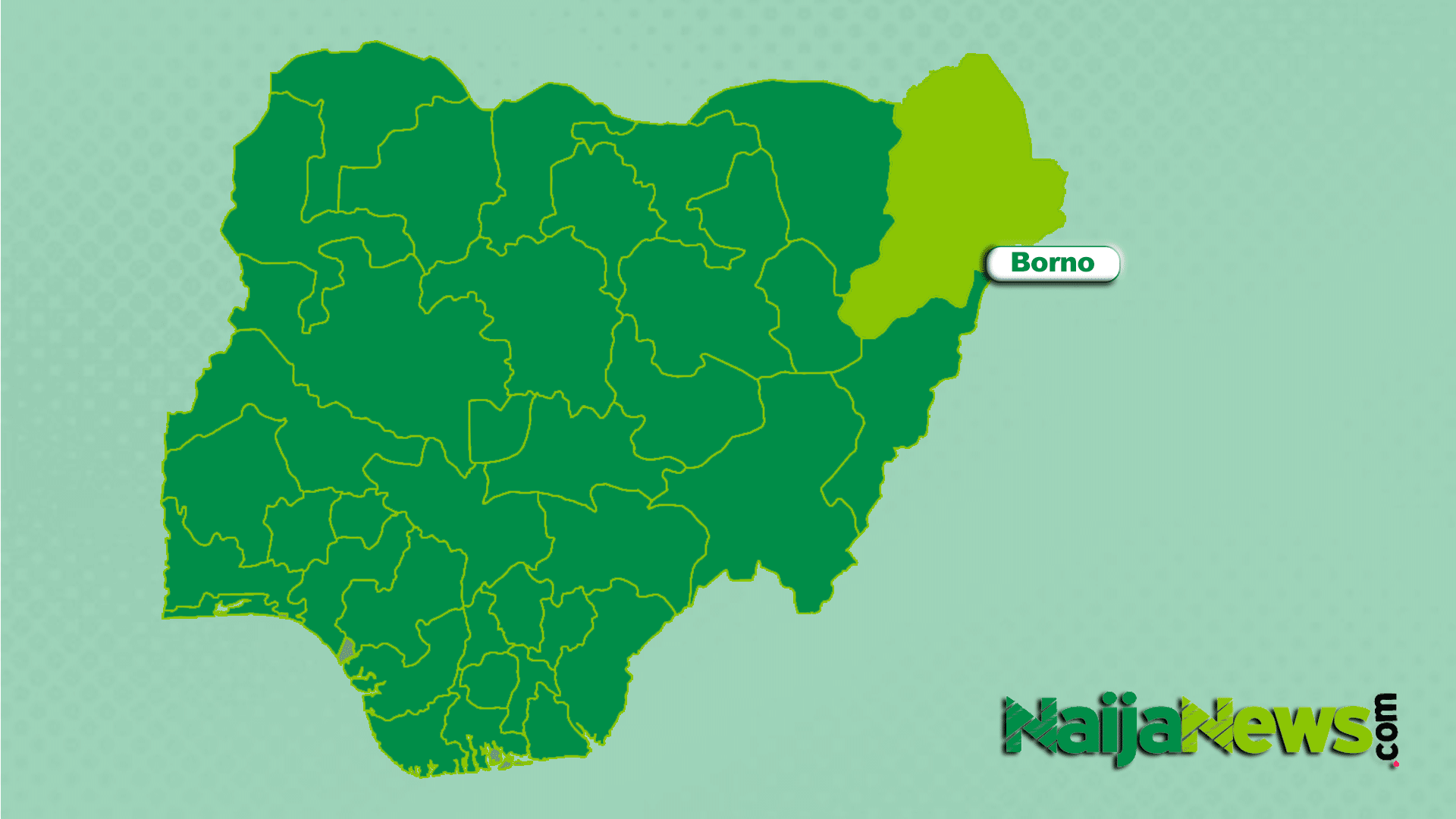

For the sake of political balance, Nigeria is divided into six geopolitical zones: South West, South East, South South, North West, North Central, and North East. Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution formally splits the nation into 36 states, designates Abuja as the Federal Capital Territory, and demarcates 774 local government areas for administration.

As with Britain, Nigeria must adapt to a rapidly changing global environment—one shaped by resurgent economic nationalism, fragmented trade, and the assertive actions of global powers.

Over the past century, Britain’s demographic diversity and the evolving concept of British identity have enabled leaders from varied backgrounds to rise to the role of Prime Minister. David Lloyd George, born in Manchester to Welsh parents, was the first Welsh-speaking Prime Minister (1916–1922). Andrew Bonar Law (1922–1923) was born in Canada to Scottish parents. Ramsay MacDonald, also of Scottish origin, led twice (1924 and 1929–1935). Jim Callaghan (1976–1979) was Welsh, while Tony Blair (1997–2007) and Gordon Brown (2007–2010) were Scottish. Rishi Sunak, the current Prime Minister, is of Indian descent.

While the majority of Britain’s leaders have been of English heritage, the pattern of leadership flowing between English, Scottish, Welsh, and more recently Indian backgrounds signals an implicit power rotation—driven by diverse voter preferences and competence.

Nigeria’s story is different. Under British colonial rule, Nigeria was created through the amalgamation of distinct northern and southern protectorates in 1914—a pragmatic strategy to expand British commercial and strategic interests. This unification brought together peoples with vastly different languages, faiths, histories, and systems of governance—without their explicit consent. The pattern repeated in other British colonies such as Ghana, India, Kenya, Pakistan, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Uganda.

The forced amalgamation generated deep-seated political and ethnic strains, which persisted before and after independence in 1960, contributed to the tragic Nigeria-Biafra Civil War (1967–1970), and continue to echo today.

The underlying issues include pervasive fears of ethnic domination by majorities over minorities—concerns examined in the 1958 Willink Inquiry, which recommended constitutional protections for minority groups, inspired by the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights. Add to this widespread corruption, maladministration, and a political landscape where competence is often sidelined for quota systems and other forms of patronage. As Dr. Uma Eleazu notes in Failed Dreams (2011), “experience and competence were compromised on the altar of indigene-ship.”

Balance, Ethnicity, and Political Dynamics in Nigeria

Nearly 65 years since independence, Nigeria’s highest offices have largely rotated between the Hausa/Fulani north and the Yoruba southwest, leaving other groups with minimal representation.

Here’s a brief chronology: Nigeria’s first Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (1960–1966), hailed from the Fulani. Major-General Aguiyi-Ironsi (1966), was Igbo; General Yakubu Gowon (1966–1975), Ngas. General Murtala Mohammed (1975–1976), Fulani; General Olusegun Obasanjo (1976–1979; 1999–2007), Yoruba. Umaru Yar’Adua (2007–2010), Fulani, was followed by Goodluck Jonathan (2010–2015), Ijaw. Shehu Shagari (1979–1983), Fulani; Muhammadu Buhari (1983–1985; 2015–2023), also Fulani. General Ibrahim Babangida (1985–1993), Gwari; Ernest Shonekan (1993), Yoruba. General Sani Abacha (1993–1998), Kanuri; General Abubakar Abdulsalami (1998–1999), Fulani. Current president Bola Ahmed Tinubu (2023–present) is Yoruba.

A closer look at leadership since independence reveals that heads of state of Hausa/Fulani heritage have led Nigeria for roughly 39% of the post-1960 period; Fulanis alone about 37%. Yorubas, 17%. Altogether, the Hausa/Fulani, Yoruba, Gwari, Ijaw, Kanuri, and Ngas nations have provided 98% of national leaders since 1960.

These statistics prompt important questions about nation-building and inclusivity: Why have the Hausa/Fulani and Yoruba dominated national leadership? Why has the Igbo group, aside from the brief Aguiyi-Ironsi interregnum in 1966, not led Nigeria? If the Igbo are still being quietly excluded because of the Biafra War’s legacy—a war that claimed nearly three million lives—doesn’t the postwar slogan “Reconciliation, Rehabilitation, and Reconstruction” sound hollow?

Democracy, by its nature, often enables majority groups and is competitive, but does this ‘winner-takes-all’ approach truly foster unity, justice, or inclusion for marginalized communities? Could Nigeria apply lessons from Britain’s quietly rotating leadership to adapt power sharing to its own complex environment?

Conclusion

This analysis aims to stir constructive reflection among lawmakers, statesmen, policymakers, and progressive thinkers. The idea: power rotation among Nigeria’s geopolitical zones can sow the seeds for greater unity, participation, and responsible dialogue with all stakeholders.

Persistent separatist movements—like IPOB in the South East, Odua nation advocates in the South West, Arewa Republic initiatives in the North, and Niger Delta republicans in the South-South—highlight the urgent need for a new approach and strong political will.

Of course, power rotation cannot offer an instant solution to all of Nigeria’s challenges. Nation-building is always an ongoing process. Yet, despite its hurdles, Nigeria remains a prime destination for foreign direct investment, boasts abundant natural and human resources, and is home to Africa’s largest petrochemical refinery and some of the world’s biggest gas and mineral reserves.

Still, the most compelling case lies in rethinking Nigeria’s foundational constitutional arrangements.

Viva Pax Nigeriana!

— Ojumu is Principal Partner at Balliol Myers LP, Lagos, Nigeria, and author of The Dynamic Intersections of Economics, Foreign Relations, Jurisprudence and National Development (2023).