Inside Zamfara’s Battle with Banditry: Can a Governor’s Resolve Match Decades of Chaos?

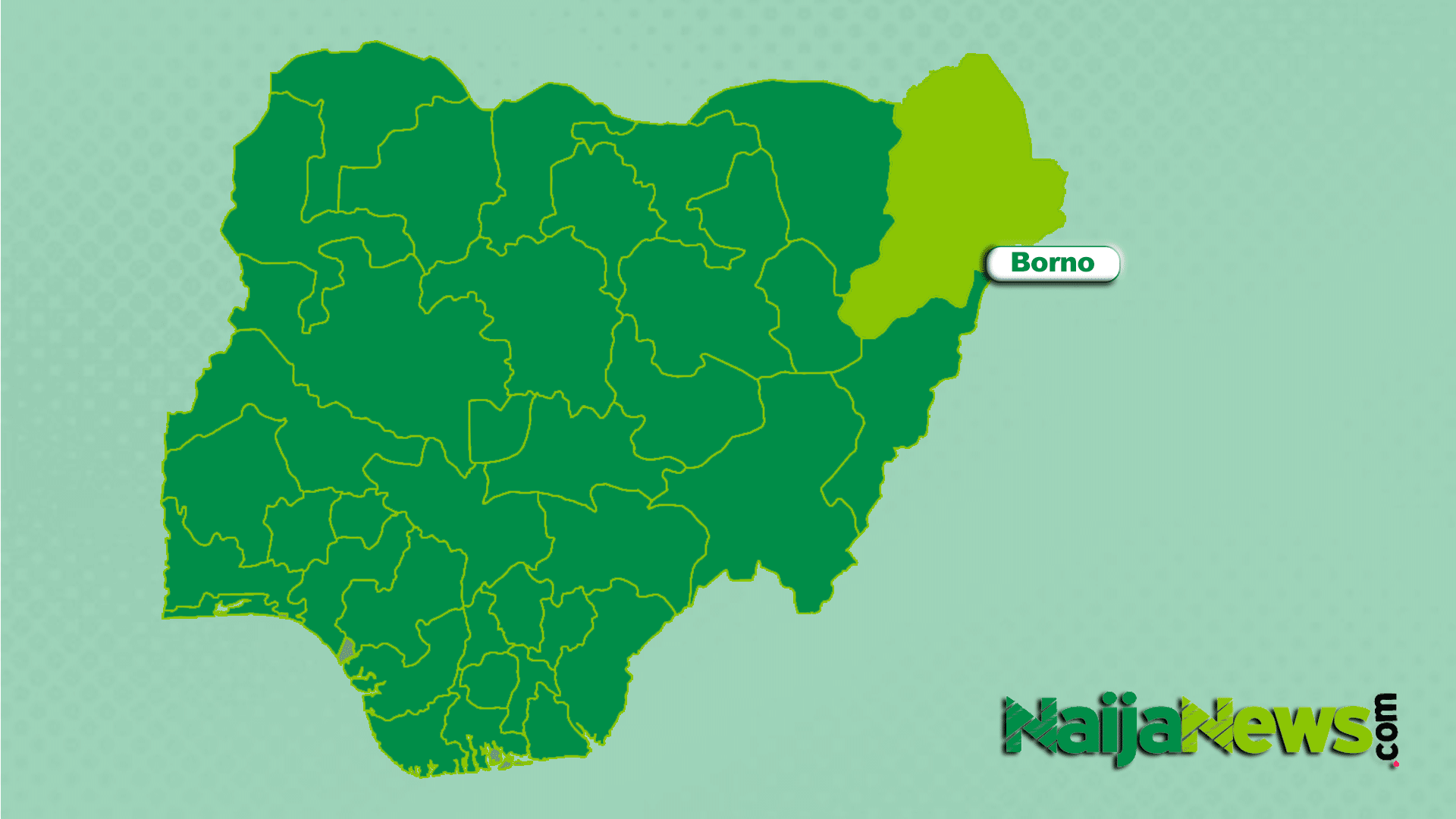

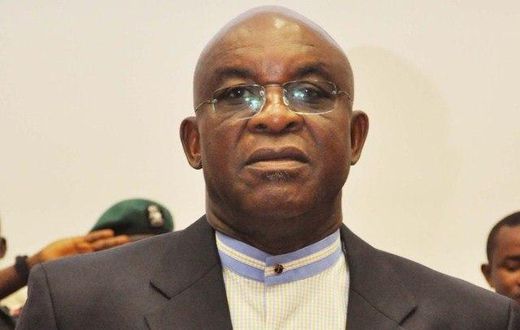

In Nigeria’s tumultuous North-West, where every headline often seems marked by violence, one name has frequently remained quietly in the background: Zamfara State Governor, Dauda Lawal. His tenure so far has largely steered clear of controversy, a necessary focus for a man leading a state that endures persistent bandit attacks and a delicate political landscape where opposition from established figures is the norm rather than the exception.

Governor Lawal has built a reputation for addressing state affairs directly and seldom engages in political quarrels—unless provoked. He reportedly reserves his public rebuttals for pointed criticisms, especially from federal politicians or rivals based in Abuja who, he believes, sometimes lack a nuanced understanding of Zamfara’s dire security reality (The Guardian Nigeria).

So, it stunned many observers last week when Lawal’s remarks made national headlines. Reacting to another surge in bandit violence that claimed at least 17 lives across Zamfara and neighbouring Katsina in just two weeks, the governor was direct: given full constitutional authority and resources, he could eradicate banditry in just sixty days—an audacious promise that triggered both hope and scepticism. (

https://x.com/leadershipnga/status/1963560779883397377?s=46&t=vSylxVmln981zHqXHRvaDA

)

How Realistic Are the Governor’s Claims?

In a candid statement, Lawal declared, “I swear to Almighty Allah, wherever a bandit leader is in Zamfara, I know. And if he goes out, I know. With my mobile phone, I can show you where these bandits are today. But we cannot do anything beyond our powers.” He added that if state governors were granted greater security powers, especially direct operational control, Zamfara would be free from banditry within two months. Yet, the grim realities on the ground suggest more complex, deep-rooted obstacles.

According to a 2022 report by Al Jazeera, between 15,000 and 20,000 people have died in banditry and insurgency-related killings in Nigeria’s North-West over the past decade (Al Jazeera). That death toll is comparable to major global conflicts and represents a devastating wound for countless families: children orphaned, homes shattered, livelihoods destroyed, and communities forced to live in anxiety and uncertainty.

In personal accounts, Lawal once recounted a missed opportunity to capture key bandit leaders. He blamed the rigid, centralized military command system—rooted in Abuja—for slowing decisive action, leaving state chief executives like himself to the role of what some analysts call “security figureheads.” According to security consultant Musa Bala, “the lack of an empowered state police force leaves governors unable to deliver real-time solutions during crises.”

The Decentralization Debate: Is State Policing the Answer?

The call for state police is gaining traction, especially in regions plagued by deadly insecurity. Still, as research suggests, Nigeria’s fight against banditry demands not just decentralization and technology but also a clearer understanding of the evolving crime landscape. A recent study conducted by the Danish Institute of International Studies and made public in August offers fresh perspectives on the complexities at play.

This report, led by Peer Schouten and Barnett James, is titled “Divided, They Rule? The Emerging Banditry Landscape in Northwest Nigeria.” It explores the shifting nature of rural violence—distinguishing bandits from jihadist groups by analyzing motivations, methods, and the socioeconomic roots of these armed networks.

Contrary to the usual narrative that lumps together bandits, jihadists, and extremists, this study reveals a more layered reality. Bandit networks, it argues, lack the ideological ambitions of jihadists but wield substantial influence over rural governance—disrupting state authority through mobile raids and systematic extortion.

Specifically, the researchers observe that, “Unlike jihadist groups, bandit networks operate without ideological ambitions, but significantly influence rural governance, challenging state authority through both roving predation and stationary extortion.” Rural communities bear the brunt, often forced to negotiate or pay for survival as formal state presence weakens or disappears.

Why Motive—and Method—Matters in Combating Banditry

The chronic insecurity is complicated by blurred distinctions on the ground. For everyday Nigerians, the difference between a bandit, a terrorist, and a criminal may seem semantic—all inflict grief, destruction, and fear. But, according to Dr. Halima Sani, a criminologist at Ahmadu Bello University, “treating all armed violence as the same invites one-size-fits-all policies that frequently miss the target.” She urges policymakers and security agencies to distinguish the criminal, jihadist, and communal dynamics to tailor effective interventions.

Therefore, for governors like Dauda Lawal, defeating banditry permanently may require not just executive liberty and security apparatus but robust understanding of the enemy’s psychology and historical context. The study underscores that unless the underlying social drivers are addressed, even aggressive crackdowns could prove futile, or worse, create unintended consequences.

Banditry: Old Patterns, New Reality

Since 2011, a combination of historical models and present-day deprivation has given rise to what the study calls “roving predation and stationary extortion.” Surprisingly, these systems echo pre-colonial patterns of governance and resource extraction once used by northern empires to maintain control and expand territory. The legacy of tribute-taking and raiding persists, albeit in the modern guise of motorcycles and mobile phones instead of horses and muskets.

Banditry, the researchers claim, mirrors the Caliphate system that once dominated Northern Nigeria—where power depended not just on religion, but also on military prowess and resource control. The report notes that today’s banditry is not the exclusive preserve of any ethnic group. It no longer relies on state-building or religious aspirations but nonetheless reflects patterns of leadership, legitimacy, and authority reminiscent of the past.

When Outlaws Fill a Leadership Void

The struggle to defeat bandit networks is made harder by their decentralized, adaptable nature. Lawal’s frustration at losing a bandit target due to military bureaucracy is not unique. While the military has scored recent victories, eliminating notorious leaders such as Baleri Fakai and Halilu Buzu, these networks are structured to survive decapitation—often replicating themselves or, according to locals, even gaining sympathy for “maintaining order” where the state is absent.

For example, after the death of Halilu Sububu, some local voices were reportedly dismayed. As stated in the report, “It was an error to kill Buzu (Halilu). He started doing good things, telling bandits to stop harassing the Fulani. He had a positive influence in Zamfara, Kaduna, Katsina, Kebbi and Sokoto.” This evolving perception illustrates how, in some cases, notorious bandit leaders transition into community guardians—complicating the narrative and strategy for state authorities.

This dynamic was on display in 2022 when Kachalla Ado Aliero, a well-known bandit, was crowned Sarkin Fulani (traditional chief) in Zamfara—a move that drew widespread concern but underlined the blurred lines between gangster and grassroots leader in desperate times.

Economy of Banditry: Survival or Greed?

The study further describes how communities, trapped between state and bandit, sometimes negotiate for survival. In 2024, kachalla Najaja’s men reportedly punished Anka town (in Zamfara) for harbouring vigilantes by preventing the harvest of millet; the desperate villagers eventually paid N50 million for “peace.” One negotiator lamented, “Our local ruler forbade us to negotiate, but he could not offer us protection nor guarantee us food.”

So, what becomes of these enormous ransoms? The research finds that bandits rarely enjoy enduring wealth. Their riches—largely made up of tributes, ransom money, and rustled livestock—are spent buying more weapons or cattle, reinforcing a cycle of power and violence. Despite the perception of bandits as “wealthy criminals,” interviews with local hunters and researchers suggest that many die destitute, their lives often ending in obscurity rather than opulence.

Long-Term Solutions: Rural Development Over Guns?

The cycle of violence, extortion, and negotiated “peace” will likely persist, the study concludes, until the federal and state governments make a sustained commitment to rural development, economic empowerment, and institutional reform. Nigerian policymakers are urged to examine not just the criminal dimensions but also the socioeconomic and historical roots of banditry—if meaningful and lasting peace is to be achieved.

For West African observers, Zamfara’s plight mirrors challenges across the region, from northern Ghana to Burkina Faso and beyond. The lessons of the past—and present—underscore the importance of combining security measures with investment in people and infrastructure.

In the end, no single leader, no matter how determined, can upend such entrenched dynamics alone. But as Nigeria and her neighbours search for answers, the voices of affected communities, the wisdom of local experts, and lessons from history must inform every step taken.

Your voice matters. What do you think: Can state governments truly eradicate banditry with more autonomy, or does the solution demand deeper social and economic reforms? Share your thoughts in the comments below and join the conversation!

Do you have a news tip or first-hand perspective on security or governance issues in Nigeria or West Africa? We want to hear from you. If you have a story to share or sell, email us at story@nowahalazone.com to get your experience featured.

For general support or other inquiries, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Stay informed—follow us for reliable updates and in-depth reports on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.